Submenu Heading

History

Butte, Montana History and Background

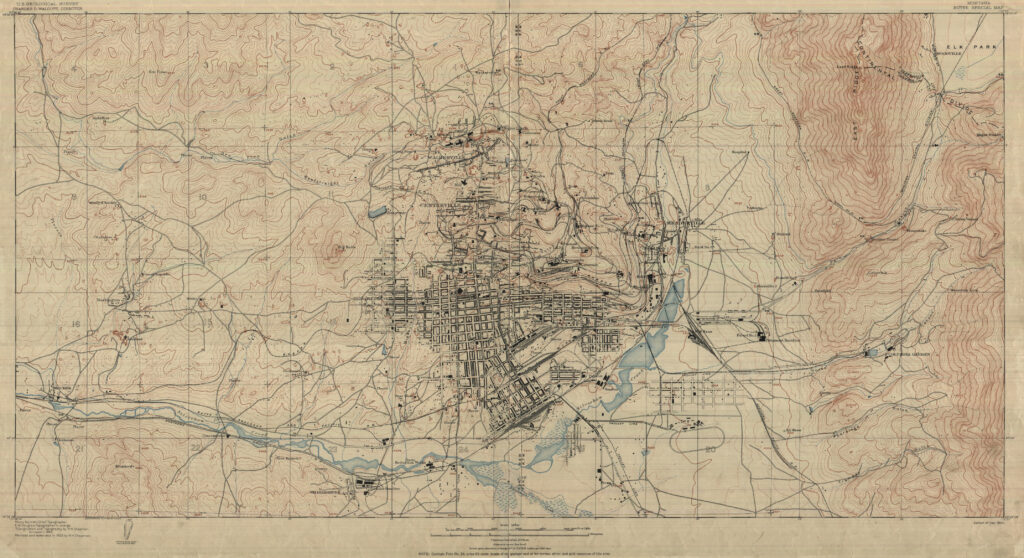

Placer gold was discovered in Silver Bow Creek, the headwaters of the Clark Fork River only a few miles from the Continental Divide in 1864. This discovery led to a stampede of placer and lode claims throughout the upper reaches of Silver Bow Creek. One of the first lode claims located was the “Parrot” lode, located in the fall of 1864. Progress for developing a mine at the Parrott was slow and it wasn’t until 1876 that one of the original locators encountered a rich vein of chalcocite. Butte had its first copper mine! The Parrot Mine, mill and smelter complex became one of Butte’s first major refining complexes and had its own extensive tailings and smelter wastes. Copper mining grew dramatically and several mills and smelters were constructed throughout the Butte townsite to process ore. In 1885 dams were built on Silver Bow Creek to contain various tailings and related processing byproducts (Figure 1). Underground mining continued in Butte throughout much of the 20th century. Upper Silver Bow Creek was severely impacted by the various tailings facilities and contaminated material had been mobilized and deposited over 190 kilometers downstream to the Milltown Dam, just upstream of Missoula, Montana by a disastrous 1908 flood. Figure 2 illustrates one of the many severely impacted areas along Silver Bow Creek in Butte.

In 1957 as the Anaconda Mining Company began work on the Berkeley Pit, one of the first large open pit metal mines, overburden was placed on top of the Parrot Tailings.

In 1977 Atlantic Richfield (Arco) acquired the Anaconda Copper Mining Company. In 1982 following the cessation of underground mining and operations in the Berkeley Pit, the underground pumps which had kept both the underground mines and the open pit dry were turned off. Water began flowing into the pit. This water was exposed to sulfide mineralization in the thousands of miles of underground workings beneath Butte. The resulting acidic metal laden waters began filling the Berkeley Pit. This water was extremely metal rich with a very low pH, 2.5.

September 18, 1983, Butte was listed as a Superfund site under the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation and Liability Act, a law passed in 1980 to address the range of environmental issues that had come to light throughout the 1970s including Love Canal among other notable sites,

After more than a century of unregulated disposal of mine waste and tailings in whatever manner and location was the most convenient and least costly, the Bill had come due (Williams, 2019). The Superfund project eventually expanded to include the Anaconda area and the Clark Fork River all the way to Milltown Dam, just upstream of Missoula, 190 kilometers downstream from Butte (Figure 3). This complex site begins with the nearly 200 billion liters of contaminated water in the Berkeley Pit and extends along the entire reach of Silver Bow Creek and as noted above extends along the Clark Fork River to Milltown Dam, just above Missoula, Montana. Throughout the city of Butte itself are situated extensive mine waste deposits related to the underground workings. Figure 4 is a detailed Google Earth view of the upper reaches of the Superfund Complex.

Figure 3. Overview of the extent of the Butte/Anaconda Superfund Complex (EPA)

Figure 4. Detailed Google Earth view of the Berkeley Pit, Upper Silver Bow Creek (yellow), Blacktail Creek (light blue) and Silver Bow Creek (dark blue). The historic channel of Upper Silver Bow Creek is shown in Orange. The Parrot Tailings are at the upper end of the yellow Upper Silver Bow Creek area.

Following its designation as a Superfund site the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) initiated Remedial Investigation/Feasibility Studies (RI/FS) to evaluate sources of contaminants and possible clean-up alternatives (US EPA, 2004).

The RI/FS led to a proposed Record of Decision (ROD) in 2005 which left considerable waste in place, including the extensive wastes left at the old Parrot site, including notably, the Parrot Tailings, an extensive tailings deposit in Upper Silver Bow Creek.